With 2025 drawing to a close, we look back on the key economic milestones that shaped the year and the insights we have highlighted, providing a clear perspective on what 2026 may bring.

Geopolitics and the new global order

Since Russia expanded its invasion of Ukraine nearly four years ago, we have increasingly emphasized geopolitics as the main driver of change in the global economy. This trend has been reinforced by growing state intervention in national economies.

This year, we have described the combination of these forces as Geopolitical Statecraft. It reflects how governments are responding strategically to a more complex and multipolar world. Rivalry, especially between the United States and China, is intensifying. National interests are increasingly taking priority over multilateral approaches, and governments are using a wide range of tools to defend them.

Technological competition, particularly in artificial intelligence, has also accelerated these shifts. Together, these forces have continued to reshape the global economy throughout 2025.

Spain’s ongoing economic momentum

While much of Europe struggles with stagnation, the Spanish economy has maintained notable growth. As early as January, we projected GDP growth close to 3% for 2025. Many of the factors that drove growth in 2024 —such as population growth through immigration, tourist consumption, and public spending— have persisted.

However, this growth remains largely quantitative rather than qualitative. In other words, it reflects more scale expansion than structural improvements in productivity or competitiveness.

Trump’s second term and the trade war

Donald Trump began his second term in late January, guided by an “America First” approach reminiscent of the Monroe Doctrine. This administration has become a clear example of geopolitical statecraft, visible in rising trade tensions and, more recently, in the use or threat of force, such as toward Venezuela.

Trade tensions escalated sharply after April 2 —dubbed “Liberation Day” by Trump— when average U.S. tariffs reached their highest level in a century. Later, Trump adjusted his global trade strategy, negotiating unilateral agreements that reduced some tariffs in exchange for other concessions. The April tariffs initially increased uncertainty, triggered financial market declines (see Chart 1), and prompted downward revisions to global growth forecasts.

CHART 1. PERFORMANCE OF RELEVANT STOCK MARKET INDICES AND GOLD IN 2025.

Source: Investing.com, Equipo Económico (Ee).

The importance of transatlantic trade

The U.S. and Europe remain the most integrated regions in the world. Trade in goods and services between the two blocs exceeded $975 billion and $470 billion, respectively, in 2024, and these flows have grown in recent years.

In this context, in the summer of 2025, the European Commission and the U.S. reached a trade agreement. Under it, U.S. purchases of European goods face a 15% tariff, while the EU imposes no tariffs and commits to purchasing energy goods and investing in the U.S.

Europe and defense

Trump’s return to the White House also brought geostrategic consequences beyond trade, including a less active U.S. role in Europe’s defense, highlighting the need to strengthen European capabilities, especially in the context of the war in Ukraine.

In June, NATO agreed to raise its defense spending target from 2% to 5% of GDP by 2035. While this increase creates opportunities, it also raises financing challenges for member states with weak budgets. The European Council recently agreed to issue joint debt to finance a €90 billion loan to Ukraine, demonstrating European commitment.

Germany and the new government

Germany, the EU’s largest economy, is heavily reliant on exports to the U.S., which accounted for nearly 23% of its extra-EU exports in 2024. The country entered this shift in the global order from a position of economic weakness, amid a combination of cyclical and structural challenges. Germany’s real GDP contracted in both 2023 and 2024.

Following the February 2025 elections, Germany’s new government passed a constitutional reform that relaxed the debt brake, allowing for increased defense spending and infrastructure investment. Other measures, such as pension reforms, aim to revive the economy amid intense intergenerational debate. Germany is expected to return to positive growth this year (0.3%), with gradual acceleration in the coming years.

Major Central Banks move cautiously toward a neutral monetary stance

In the euro area, modest growth and inflation near the 2% target led the ECB to cut policy rates by 100 basis points in the first half of 2025. Later, with expectations of a mild recovery and upward risks to inflation, rates remained unchanged. The ECB may hold them steady over the next two years.

The U.S. Federal Reserve kept rates steady in the first half of 2025 due to tariff-driven inflation. In the second half, the Fed cut rates by 75 basis points, seeing the tariff effects on prices as temporary amid a slowing economy. Looking ahead to 2026, the succession of Jerome Powell, whose term ends in May, will be critical, along with concerns about central bank independence amid repeated political pressure.

Fiscal policy, public debt, and sovereign bond markets

Following successive crises in recent years and greater state intervention in national economies, global public debt remains historically high at 97.6% of GDP in the first half of 2025. Major economies, including the U.S., China, the UK, Spain, France, and Italy, have weakened fiscal positions, leaving limited room to respond to economic shocks or rising spending pressures, such as those from aging populations and defense. Germany remains in a stronger position.

Against this backdrop, sovereign bond markets have become increasingly sensitive to fiscal risks. After an initial increase in yields on U.S. sovereign debt earlier in the year, French government bonds have seen the largest rise in yields throughout 2025, even trading above Italian bonds. France faces a fragile fiscal position, with the largest euro area deficit in 2024 at 5.8% of GDP and the third-highest debt ratio at 113.1%. Political instability compounded these risks after September, and by year-end, the 2026 budget was still in progress under the new government.

Spain’s fiscal risks and regional public finances

The Spanish public deficit is expected to shrink in 2025 thanks to strong economic growth and increased tax revenues, but spending efficiency remains unaddressed. Although the debt-to-GDP ratio fell to 103.2%, this reflects nominal GDP growth and higher prices, not a reduction in absolute debt, which reached €1.7 trillion in Q3.

Legislative paralysis compounds these challenges. The government has not passed a new budget since the end of 2022. It is increasingly likely that the entire legislative term will pass without new budgets. This not only limits consolidation capacity but also hinders the implementation of structural reforms. Looking ahead to a potential 2026 budget, Congress has already twice rejected the budgetary stability targets for 2026–2028. The approved spending ceiling for 2026 reflects an 8.5% increase to €216.2 billion, up 69.5% from 2019 when excluding European funds, challenging fiscal prudence.

Spain’s autonomous communities must share responsibility for fiscal consolidation. The Spanish regional debt stands at 21% of GDP, the highest in the EU among countries with strong regional powers. Many regions rely on state financing, with 60% of regional debt held by the state through Regional Financing Funds. Only seven regions have issued bonds since January 2024.

In the absence of a long-overdue reform of the regional financing system, pending since 2014, measures like partial forgiveness of regional debt without strict conditionality risk worsening fiscal discipline. Any state assumption of regional debt should include firm guarantees of future consolidation.

Structural imbalances in Spain

Spain faces imbalances that hinder per capita convergence with Europe. These include persistently high unemployment -the highest rate in the euro area at 10.5% in October-, and weak business investment, which is crucial for productivity growth and has yet to recover from the pandemic amid elevated uncertainty.

There is also a mismatch between insufficient housing supply and strong demand, with supply constrained by regulatory bottlenecks, labor shortages, weak incentives, and regulatory uncertainty. The most visible consequence of this imbalance is the sharp rise in housing prices, up by 12.8% year-on-year in nominal terms in the third quarter.

External competitiveness in services

Spain has a significant structural advantage in this environment of high uncertainty: strong external competitiveness. Clear evidence of this is the country’s sustained external financing capacity for nearly fourteen years. This has been driven primarily by services, both tourism and non-tourism. Estimated tourism revenues for 2025 are equivalent to Spain having almost 10 million additional consumers.

By contrast, goods trade has been more adversely affected by the international environment and rising costs.

EU opportunities, the Mercosur agreement, and Argentina

Structural challenges in the EU could become growth drivers if addressed strategically. External threats are driving deeper integration and stronger autonomy. Focusing on innovation and technology must be accompanied by removing barriers in the single market, increasing labor flexibility, improving the business environment, and advancing a capital markets union. Budgetary efforts should prioritize defense and energy.

The EU should also strengthen integration with third countries, notably through the EU–Mercosur Agreement, which aims to create a market of 700 million consumers. Political closure occurred in December 2024 after 25 years of negotiation, but 2025 ends without provisional ratification, delayed again to January 2026.

Among Mercosur countries, year-end expectations have improved for Argentina following the volatility surrounding the October midterm elections. The country now faces the challenge of meeting its stabilization program and implementing reforms. So far, it has successfully issued a dollar-denominated bond and is already debating labor reform in its parliament.

Markets and the real economy

As trade war uncertainties eased, abundant liquidity, technological investment, and investor optimism pushed major stock indices close to all-time highs. Yet macroeconomic forecasts still point to slowing global growth. OECD projections show U.S. growth at 2.0% in 2025 and 1.7% in 2026, down from 2.8% in 2024. For the euro area, growth is 1.3% in 2025 and 1.2% in 2026.

This gap has fueled debate over whether financial markets reflect real economic fundamentals, with financial volatility expected to rise further in 2026.

Outlook for the Spanish economy in 2026

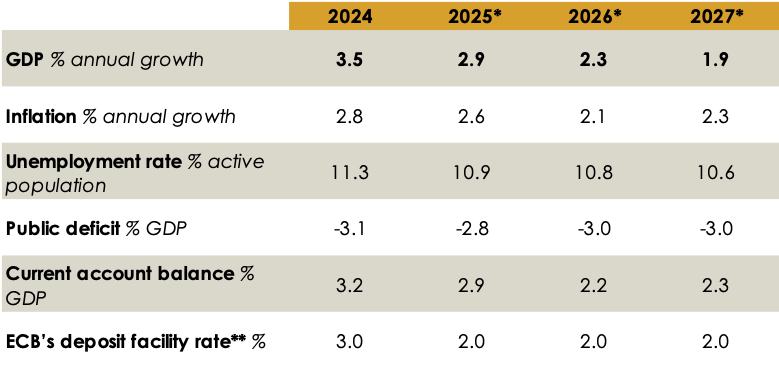

After 2.9% growth in 2025, we expect the Spanish economy to maintain a strong pace of expansion, which we estimate at 2.3% (see Table 1). Based on the latest available data, we are likely to revise this forecast upward in the coming weeks, particularly thanks to strong household consumption, rising employment from population growth, and higher public spending in an electoral context. Tourism continues to play a key role, setting records on arrivals and spending despite moderating growth.

TABLE 1. MACROECONOMIC FORECASTS BY EQUIPO ECONÓMICO (Ee) FOR THE SPANISH ECONOMY.

(*) Equipo Económico (Ee) forecast. (**) ECB deposit facility rate at the end of each year.

(*) Equipo Económico (Ee) forecast. (**) ECB deposit facility rate at the end of each year.

Source: INE, Bank of Spain, Equipo Económico (Ee).

For this growth to translate into stronger potential growth, greater sustainability, and increased per capita convergence with Europe, it would be necessary to advance a series of reforms aimed at correcting persistent structural imbalances. However, this effort is severely constrained by the current political landscape.

We thank you for your trust in our professional services firm and wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year 2026.

Director for Economic analysis and International affairs, Equipo Económico (Ee).

Senior Economic Analyst – Economic analysis and International affairs, Equipo Económico (Ee).

Economic Analyst – Economic analysis and International affairs, Equipo Económico (Ee).